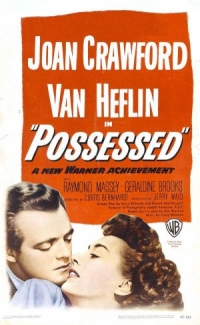

Possessed (1947)

Directed by Curtis Bernhardt

Screenplay by Silvia Richards and Ranald MacDougall

Runtime: 1 hr, 48 min

It’s no secret

that our own judgments and perceptions can be flawed. This is especially true regarding how we

perceive our own conditions and personalities.

We don’t see when we are acting cruelly or giving mixed signals, as what

we mean to say is clear to us. Even if

we can see the same problems in others, finding them in ourselves is another

story entirely. Throw in some mental

instability and the endeavor is nigh impossible. Throw all of that on the screen, and you get

this week’s movie, Possessed.

Possessed

begins with a confused woman named Louise (Joan Crawford) wandering the streets

of Los Angeles, repeating the name “David” to passers-by. Brought to a hospital psychiatric ward and

prompted by Dr. Willard (Stanley Ridges), Louise spits her story in

flashback. She was a nurse under the

employ of one Dean Graham (Raymond Massey) to care for his ailing wife. More importantly, she was madly in love with

a man named David Sutton (Van Heflin), who broke off their relationship. Simply put, Louise would do anything to keep

David with her. This sort of thing

cannot end well.

When we first

see Louise and David together, they are at a house across the lake from Graham’s

summer home. It is at this point that

David wants to break things off, and their relationship is established

expertly. Crawford’s voice is

particularly upbeat as she dresses, but Heflin shows that David’s thoughts are

not with Louise; he is clearly more focused on the music he’s playing than his

lover. As David breaks the news, the

tone becomes increasingly awkward, the silences more frequent, and Crawford’s

delivery more desperate. Her later

madness is made understandable in this scene.

Further, this

scene foreshadows the excellent performances in Possessed. Crawford shifts

from being confident and happy to visibly holding back the tears to mentally

unstable with fluidity, to the point that what her character feels at any

moment can only be described as “muddled”.

Her excellence extends to her scenes in the hospital, where the fatigue

on her face is palpable and confusion is pronounced yet restrained. The work that Crawford put into studying the

behavior of mentally ill patients is evident, and it pays off in spades.

As for the men

in her life, both Heflin and Massey succeed in their very different

portrayals. Heflin brings a degree of

impersonal calculation to his character—appropriate, considering his obsession with

mathematical engineering. He appears

level headed, but it hides a tinge of unknown unkindness. Massey, on the other hand, gives Graham a

justified level of dignity, but there’s the feeling he’s suppressing some

emotions, especially after proposes to Louise a year after his wife dies. It’s the same sort of performance that made

Massey shine in Abe Lincoln in Illinois

and the saving grace of The Fountainhead.

Crawford is the

star, however, and it is her character that drives things. What is being driven, however, is not always

clear—but this is to the film’s benefit.

First of all, the story is told via the flashbacks of a character that

clearly is not all there. The doctor

himself notes that Louise is very vulnerable to suggestion, and while he doesn’t

apply it to her spiel, one need not tax the imagination to believe the whole

story, which the doctor is prodding, is in doubt. All we can say with certainty is that she did

in fact marry Dean Graham; the rest would require some investigation.

Even within the

flashbacks, however, the difference between perception and reality is front and

center. Despite being a nurse who can

clearly see Mrs. Graham is mentally ill and imagining things which aren’t so,

Louise is unable to see the same problems in herself until explicitly

told. A five minute sequence, in which

Dean’s daughter Carol (Gerladine Brooks) tells Louise that David knows that she

killed Mrs. Graham, is completely false and detached from reality. Of course, whether Louise is even having

these delusions is debatable; she claims to see Mrs. Graham, but the audience

never does.

Possessed,

then, makes for an interesting look at perception, delusions and other

psychological phenomena. Oddly, though,

the explicit psychology that Dr. Willard delivers is the one stumbling block of

the film. The flashbacks are interrupted

periodically for the doctor to make his diagnoses. Not only is this distracting to the story,

but also it is delivered with such conviction and certitude that it’s pretty

damn laughable. It most reminds me of

the last five or so minutes of Psycho;

surely this must have sounded better on paper.

Psychobabble

aside, Possessed proves to be an

intriguing drama which, in its own way, forces one to reconsider the way in

which we perceive the world around us.

How open are we to the suggestion of others? Why is it that we see the flaws in others so

clearly, yet can’t find those same problems in ourselves with a GPS? This is not a film that provides answers to

those questions—after all, it is a movie, not a psychology textbook—but we

cannot seek out the answers unless we know the questions to ask.

No comments:

Post a Comment