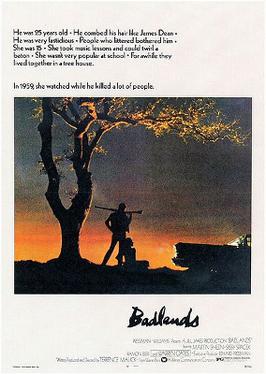

Badlands (1973)

Directed and written by Terrence Malick

Runtime: 1 hr, 34 min

I first became

acquainted with Terrence Malick through the beautifully pretentious and

liberating film The Tree of Life. That movie put Malick on the “watch whatever

he has directed” list. But as I discovered,

there are not all that many films that he has directed. In fact, even though his directorial career

starts in the early 1970s, The Tree of

Life was only the fifth film under his belt. Certainly that makes him easier to catch up

on than, say, Michael Curtiz or George Cukor.

And what better place to start than at film number one, Badlands.

Loosely based on

the Starkweather homicides (thank you, Billy Joel), Badlands casts Martin Sheen as Kit, a garbage collector in South

Dakota. Kit, who’s in his mid-20s, falls

for the fifteen-year-old Holly (Sissy Spacek); the two try to keep their

relationship a secret, but when Holly’s father (Warren Oates) finds out, things

turn ugly very quickly. Kit shoots the

father, sets the house on fire, and takes off with Holly. They spend the rest of the film on the run as

Kit piles up an ever-growing body count.

With all that

murder and the constant fear of getting caught, one might expect Badlands to be an emotionally charged

film. Certainly there are a lot of

emotions bubbling below the surface, but the presentation of the film is

remarkably restrained. Spacek’s

narration throughout is delivered almost disturbingly matter-of-factly, and the

actors find themselves in a nearly continuous state of numbness. At times it almost feels like the film is a

story being told by a history teacher, rather than a tale of a crime spree.

However, while

that feeling is present, I think the presentation ultimately works to the films

advantage. Had the emotions been more visible—more

screaming and crying, for instance—then it would have certainly been more

movie-like. But the more restrained tone

allows the audience to explore the characters on a deeper level, which is more

or less the film’s goal. With very

limited amounts of action, the relationship between Kit and Holly is brought to

the forefront, and the long moments of inaction present them at default state.

The emotional

distance in Badlands is particularly

beneficial for Sheen’s Kit. There may

have been a temptation to play Kit as a sociopath. Well, he is, but Sheen doesn’t make that the

focus of his performance. His actions

may demonstrate his mental issues, but he is not defined by his bloodthirsty

ways. If anything, it’s something he’s

grows into, as Sheen’s character does not always seems aware of what he’s

doing. Further, and more importantly,

it’s not his sole motivation; his affection for Holly, after all, it what

triggers the crime spree in the first place.

Holly,

meanwhile, goes through a lot beneath her flat expressions. Initially, she is quite clearly drawn to

Kit’s whole James Dean clone persona, but there is an element of

self-deprecation in her narration as she describes life before the death of her

father. There may be genuine affection

for Kit at first, but she gradually falls into staying because, well, what

other options are there? Her face seems

to be holding back tears towards the end, and she goes from reading Kit a warm

narrative in there tree house to the dry celebrity gossip column of a magazine

on their way to the border.

The actors and

the story tend towards the subdued, and the cinematography furthers this

feel. On the one hand, some of the

sequences are absolutely beautiful: a bright full moon against a clear sky,

that one mountain way in the distance that appears ever so closer, etc. It is all so lovingly shot, yet it also

creates an overwhelming sense of loneliness (or as Kit prefers,

“solitude”). This is not to say that the

film creates the illusion of there being no way out. Rather, than gorgeousness and loneliness

combine to create an oddly blasé texture to the proceedings.

You know, the

word “indifferent” might be a good descriptor of the film. Not in the sense that I didn’t care what was

happening—or that the filmmakers didn’t, either. No, I mean that there’s no sense that Malick

or anyone else had a particular message or point to send. There was simply a story of two people to

tell, and everything else involved in the production is merely

window-dressing. This can make Badlands more than a little alienating,

but it also makes the film commendably fair and direct—no one’s beating around

the bush here.

Malick, both in

the script and on the screen, neither condemns the two fugitives nor holds them

up as some misunderstood rebels. That

may be the greatest strength of the indifferent tone of the proceedings: it

portrays Kit and Holly as people without passing judgment. I could neither root for them to elude the

authorities nor desperately want them to be caught. Again, to many viewers this might be a major

demerit—I certainly get the desire for a rooting interest—but I do appreciate

the ambiguities. In fact, that may be

all that a film needs.

No comments:

Post a Comment