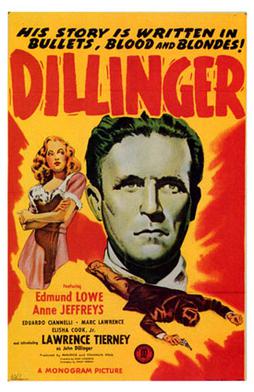

Dillinger (1945)

Directed by Max Nosseck

Screenplay by Philip Yordan

Runtime: 1 hr, 10 min

I’m never sure

what to make of America’s fascination with gangsters and bandits. Do people view them as Robin Hood

analogues? They do like targeting the

major financial establishments, even if they aren’t spreading the spoils. Maybe we view these fellows as tragic

figures, people who rise in some field but are done in by some personal flaw. Or it could just be their use of violence;

man is fond of violence. Whatever the

reason, it’s clear that this interest exists.

Why else would there be at least three different films about John

Dillinger simply called Dillinger?

The version I

saw, which I’m told plays fast and loose with the historical record, finds Lawrence

Tierney as the infamous bank robber and Public Enemy No. 1. Arrested for robbing a grocer of $7.20,

Dillinger is sent to prison, where he joins up with a gang of robbers led by

Specs (Edmund Lowe). Once they’re all

out of prison, they set out doing what they do best: robbing banks. Along the way, Dillinger enters a

relationship with a movie ticket saleswoman named Helen (Anne Jeffreys), who,

you guessed it, Dillinger robbed.

I realize that

this is a movie about a robber, but, well, there’s too much robbing in it. Whether it’s that poor grocer or the Farmers

National Bank, there is simply too much time spent on the direct criminal

aspects of the story. The audience is presumably

familiar with John Dillinger’s exploits; I doubt anyone going in thought he was

a congressman. The bank robbing is the

obvious, and hence least interesting, part of his legend. A better question would be, “Who exactly is

John Dillinger, and why’d he get into crime?”

The film doesn’t

really answer that question. Tierney

doesn’t bring a whole lot of depth to the character; all I can gather is that

Dillinger is in a near constant state of annoyance. On top of that, Dillinger gets into crime

very quickly and for seemingly no reason.

One night out drinking he doesn’t have cash on him, so he holds up a

grocer…and now he’s a hardened criminal.

I get the feeling that, even if that is how the physical events played

out, there’s a lot of footage missing from that sequence. Unless he just snapped, of course, but that

raises the question, “Why?”

The origins of

“John Dillinger, Master Stick-Up Artist” may not be explored at all, really,

but I will give the film credit for crafting a nice narrative for his rise to his

gang’s leadership position. Specs begins

as the double-share-taking head honcho, but compared to Dillinger, he’s a

tactical conservative: pass up the highly secured banks, keep the body count as

low as possible, etc. Dillinger, by

contrast, is the group’s daredevil.

He’ll target the big money and is none too cautious with his arms. He’s the group charismatic leader, if you

will, and that gets more attention than careful strategy.

Not to say that

Dillinger himself isn’t a conniving mastermind; he’s just one willing to assume

massive risks. This can be seen in the

famed escape from prison using a hand-carved wooden gun, perhaps the best scene

in the film, and in his thorough casing of the Farmers National Bank. Smart and full of swagger, he’s a legitimate

threat to Specs’ authority in the gang, and the tension between the incumbent

and the challenger propels the action forward, even if the resolution of this

tension is somewhat contrived—the dentist gets involved in the mess.

That Dillinger is at its best when it focuses

on the group’s internal politics is somewhat problematic, however. Once Specs has been permanently removed the

equation, the remainder of the film falls flat.

This is because Dillinger’s relationships with all of the other

characters, from Helen to his new subordinates, are not very well developed. They just serve as tools and obstacles to his

ends. Once his main rival has been taken

care of, it’s “John Dillinger vs. the Authorities”, and I can’t help but root

for the cops here.

In fact, that’s

another boat anchor around the film: we know that Dillinger is going to die,

where he’s going to die, and a whole bunch of other details. Unless the lead up is of particular interest,

that inevitably overrides the goings-on.

I know that once the politics had been swept away, all I was moved to do

was wait for that fated showing of Manhattan

Melodrama. Had Dillinger as a

character been more compelling or perhaps the action a bit more grabbing, that

feeling could have been averted. Instead

it’s like waiting for the guillotine to drop—or, rather, for the cops to show

up.

Granted, this

came out in 1945—maybe the allure of John Dillinger really was that powerful a

little over a decade after his death that his mere presence was compelling

enough for a film. If that’s the case,

then it can be considered a product of its era. And, no, this is not a film that really fails

at filmmaking. But if this film served

as the only evidence of Dillinger in the historical record, I’m fairly certain

that historians would be confused as to how to explain his place in the

American consciousness.

No comments:

Post a Comment