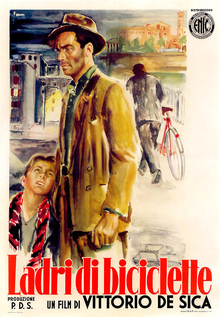

Bicycle

Thieves (1948)

Directed by Vittorio De Sica

Screenplay by Cesare Zavattini,

Suso D’Amico, Vittorio De Sica, Oreste Biancoli, Adolfo Franci and Gerardo

Guerrieri, based on the novel by Luigi Bartolini

Runtime: 1 hr, 29 min

In

my hobby of watching classic cinema, one conclusion I have arrived at is that

the most fragile situations are always the most heartbreaking. Whether it’s the car engine sequence in

Charles Burnett’s Killer of Sheep or

the slowly dissolution of the doorman’s psyche in The Last Laugh, nothing brings about depression quite like life

slipping off the tightrope. Today’s

picture, the first picture to ever top the prestigious Sight & Sound poll of the greatest films of all time, most

certainly fits into that particular mold.

The

name of the film is Ladri di biciclette,

literally Bicycle Thieves. Though often translated into English as The Bicycle Thief, that title is a bit

misleading; there is more than one such character in the film. Our protagonist is Antonio Ricci (Lamberto

Maggiorani), a struggling family man in post World War II Rome, has just found

work placing posters around the city. It

has given him the chance to provide for his wife, Maria (Lianella Carell) and

his young son, Bruno (Enzo Staioli). On

first day on the job, however, his bicycle is stolen; unless he can recover it,

he is going to lose the position.

Losing

the bicycle is devastating for Ricci.

That we see the build-up to moment makes it even more wrenching for the

audience. From the Ricci’s cramped

quarters to the throng of people in the opening sequence desperate for work,

the film’s universe is riddled with poverty.

Just acquiring the bicycle involves tremendous sacrifice for the

family. Ricci had previously pawned his

bicycle, so Maria pawns off the bed sheets from her dowry to raise the money to

buy it back. Even then, they don’t get

all that much from it: 7,500 lira, less than what Ricci would make in one month

pasting up posters.

And

then, in one fell swoop, it’s all for naught.

Someone pilfers the bicycle before Ricci can react. It’s a position of hopelessness and weariness

which Maggiorani portrays beautifully.

Despite, like the rest of the cast, being an amateur actor, Maggiorani's performace

is completely convincing. His demeanor

is bleak throughout most of the film, oftentimes frustrated and occasionally

rage-filled. Yet, every once in awhile,

he is able to reach down and find something, even the most insignificant thing,

to smile about.

Equally

as powerful is Staioli as Bruno. Unlike

his father, Bruno has yet to be beaten down by harshness of lower-class

Italy. He’s ecstatic to give his

father’s bike a cleaning before his first day of work, and has the mental

acuity to instantly recall the serial number when they go searching for it in

the markets. This is not to say that

Bruno is never depressed. Far from it—in

fact, he probably has a wider range of emotions than Ricci. He is the mirror for the audience, reacting

to the plight of his father as best as someone his age can. In this sense, then, Bruno is the heart of Bicycle Thieves.

As

wonderful as the two leads are, the real star of the film is post-war

Rome. Virtually the entire city is in

some way desperate. The apartments are

all cramped, the police are unresponsive and the unemployment office is in way

over its head. All of it beautifully

photographed, with intimidating empty space for the exteriors and deep gray

shadings indoors. Some of it borders on

expressionist, but grit underlines nearly every frame. The Rome of Bicycle Thieves is most definitely the place where as stolen bike

really is a matter of life and death.

Of

course, good luck telling the picture’s aristocracy that. Even more heartbreaking than the loss of

Ricci’s bicycle, to me at least, is the indifference of the wealthy. Two instances stand out. First, when Ricci first reports his stolen

bicycle to company, the man in charge just shrugs and tells him to look for it;

when another worker asks what’s been lost, he replies, “Nothing. Only a bicycle.” There’s no reason for the boss to bother

doing much, since there’s no shortage of unemployed men with bicycles. What gets lost, though, is Ricci’s

humanity. Only a bicycle, indeed.

The

second incident, involving Bruno, is even more gut-wrenching. At one of the few happy sequences post-theft,

Ricci and Bruno stop in a restaurant to get food. The clientele is much for refined and the

waiters clearly look down on the two.

But what is most unnerving are the looks that Bruno keeps getting from

the rich family having lunch at the table behind them. Ricci attempts to reassure his son, but their

presence only reminds the father of all the money, of the promise of a stable

life, that the stolen bicycle has robbed him of.

So,

in conclusion: Bicycle Thieves is the

sort of film that, when you've finished watching it, makes you hope somewhere

in the back of your mind that you accidentally walk in front of a speeding

train. When even the momentary reprieves

from the daily grind serve to remind the protagonists that their lives are

broken, you know that the Earth is actually a cold dark place. I cannot stress how moving Bicycle Thieves is as a motion

picture. Just make sure you keep several

boxes of tissues on hand for the last ten minutes. Fair warning to you, there.